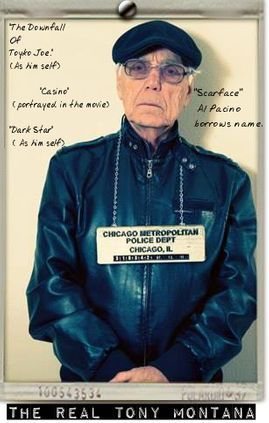

R.I.P. THE ‘REAL’ TONY MONTANA

Tony Montana was nothing like the film version portrayed by Al Pacino in the mob classic “Scarface.”

He was a low-profile mob associate – a watch dog – for the really bad guys like Las Vegas enforcer Tony Spilotro and Chicago crime boss Sam Giancana.

If the Chicago outfit needed somebody inside to keep a restaurant or brothel profitable, Tony Montana was their man.

He was so low-key I lived in the same residential tower for nearly 20 years unaware the short guy in his 80s with a little dog had mob connections.

I never saw him without his constant companion, Eliza, his black pug named after one of the stars of the Broadway hit, “My Fair Lady.”

Our introduction happened about a year ago. It was 2 a.m., in the driveway of the Regency Towers at Las Vegas Country Club. We were taking our dogs out for their last potty run of the day. My Silky Terriers, Rumor and Scandal, had bonded with Eliza from day one. I introduced myself and immediately recognized his name.

I told him about a telephone conversation I had in 1988, when I was working on a sporting betting investigative story while working for the Rocky Mountain News in Denver. The Denver Broncos had lost the Super Bowl to the New York Giants and, it turned, some Bronco fans lost their houses.

During the conversation, I told Montana I had called a sports betting 800 number and the person I talked to identified himself as "Tony Montana." Montana just smiled.

I told him we should have lunch one of these days. “You know how to reach me,” he said.

It came a shock over the weekend to read his name among the obits. Several mutual friends confirmed it was my neighbor.

He had received some dire medical news recently and was in the process of taking care of his end-of-life matters when he died April 18. The Chicago native was 85.

In their 2014 book “The Real Tony Montana,” co-author Nathan Nelson wrote the long-time Las Vegas resident “never robbed or killed anyone, he wasn’t a loan shark or an enforcer or a thief, however, he did work for some of the biggest names in the history of organized crime…and lived to talk about.”

However, Montana was no choir boy. He spent two years in Boron Federal Prison at Edwards Air Force Base from 1986 to 1988 after being swept up in a sting operation targeting organized crime member operating throughout Las Vegas. He was convicted for credit card fraud, possession of stolen property and counterfeiting.

One of my favorite stories in the book involves Spilotro putting Montana in charge of Villa D’Este restaurant, now known as Piero’s Italian Cuisine. Villa D’Este was formerly known as Coach and Six and was owned by Giancana, who had turned over the restaurant to his longtime chauffeur and private chef, Joe Pignatello, as a gift.

Spilotro set up a meeting between Montana and Pignatello to establish the ground rules after Pignatello borrowed money from the Chicago mob.

The Chicago boys wanted Spilotro to keep his eyes on their investment. The restaurant became the headquarters and Spilotro and his “Hole-in-the-Wall” Gang.

Spilotro was letting Pignatello know the restaurant was now under his control and said Montana “is here to make sure this place is running the way it should and to watch my money.” He added Montana, “is very good at what he does.”

Montana was rewarded with a condo Spilotro had at Regency Towers.

Pignatello ran a tight ship.

Singer John Davidson wanted to pay at the end of his 30-day engagement at the Hilton. Joe Pig said no. Los Angeles Dodgers manager Tommy LaSorda asked for his party of eight dinner to be comped. No dice, said Pignatello.

Even Frank Sinatra and the star-studded group he brought in had to pay $200 per person for a $9,000 check.

According to the book, there was an occasional exception. One day a busload of nuns from Spokane, Washington pulled up to the restaurant. They were on a fund-raising tour and wanted to know if they could get a discount for dinner. Montana went to Spilotro with the request.

The nuns ate free. Well, not exactly. Spilotro asked them to sing for their supper. He invited members of his crew to show up for the brief performance.

Spilotro instructed Pignatello to pass the hat around the tables to help the nuns out.

According to the book, $47,000 was collected.

A few weeks later, a plaque arrived from the nuns, thanking Spilotro and Pignatello for their generous gesture.